A Look at the History of Chinese Restaurants in Columbus

Our search for the first Chinese restaurant in the city, plus local food news

Song Lee and Sun Joiy Were Among the First Chinese Restaurants in Columbus

By Bethia Woolf

Last year, Ding Ho Restaurant on Columbus’ West Side received a lot of attention in the local media after New York-based video creator Rob Martinez featured its egg rolls and wor sue gai in one of his videos. At last count, Martinez’s video had 5.9 million views on YouTube and almost 2,500 likes on Instagram.

When Curt Schieber (tour guide, DJ and author of “Columbus Beer”) read the articles about Ding Ho being the oldest Chinese restaurant in Columbus, he was surprised and emailed me to see if I knew anything about the history of Chinese restaurants in Columbus.

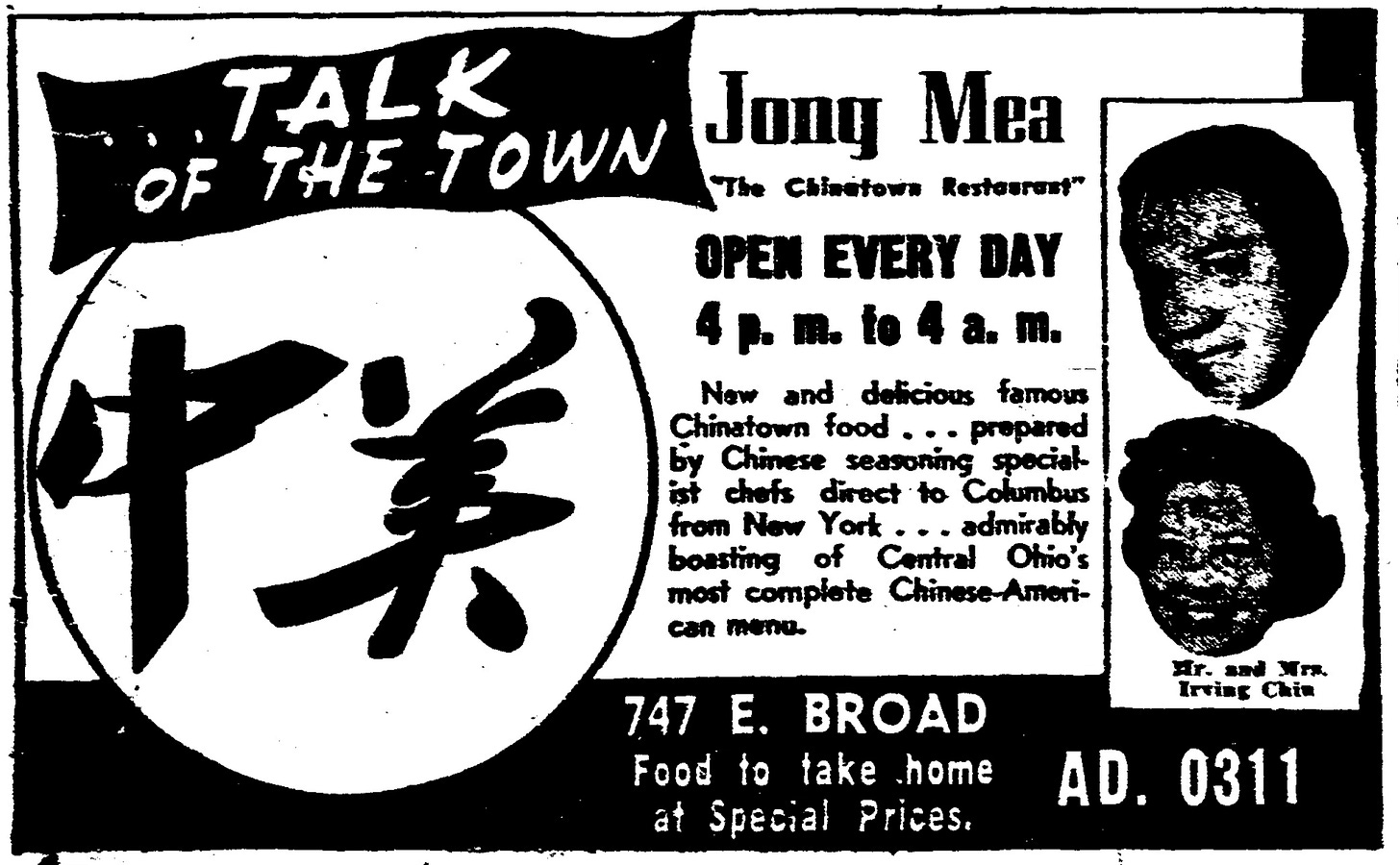

“I realized that I had missed [Ding Ho] when I first came to Columbus in October 1974,” Curt wrote. “I remember lamenting at the time that there was only one Chinese joint in town, Jong Mea. My friends and I went there often, especially late, after the clubs closed. Imagine my surprise recently, when I read about Ding Ho opening in 1956! ‘How did I miss it,’ I thought. ‘Was it really older than Jong Mea?’ ”

Curt’s email made me curious about the history of Chinese restaurants in Columbus, and I wanted to know: What was the first Chinese restaurant in the city and when did it open?

Ding Ho Restaurant is often cited as the oldest operating Chinese restaurant in Columbus, but I discovered it was far from the first Chinese restaurant in the city. With the help of Columbus Library staff, I have been poring through old Columbus Dispatch newspaper archives, clippings and city directories to find the earliest mentions of Chinese restaurants or "chop suey joints," as they were commonly called at the time. Based on my research, Chinese restaurants in Columbus date back to at least 1902.

Indeed, Chinese restaurants have been an integral part of Columbus' history for over a century, evolving from early chop suey houses to the diverse range of regional Chinese restaurants we see today, such as Jiu Thai Asian Cafe, NE Chinese Restaurant, ChiliSpot and others.

Here’s a look into that history.

Chinese Immigration in the U.S. & the Rise of Chinese Restaurants

There were two main waves of Chinese migration to the United States, with a long gap between them. In the mid-1800s, primarily male laborers arrived on the West Coast to work in mining, railroad construction and other manual labor industries, including farming. However, the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 severely restricted Chinese immigration and prohibited Chinese residents from obtaining U.S. citizenship.

The exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants were finally repealed in 1943, but large-scale immigration did not resume until the mid-1960s, when the 1965 Immigration Act reopened migration pathways for non-European immigrants. Chinese immigration increased even further after the U.S. and China normalized diplomatic relations in 1979 under President Jimmy Carter.

This context is intriguing because Columbus had a significant number of Chinese restaurants opening during a period when immigration was minimal. Presumably, many of these restaurant owners were second-generation Chinese Americans whose families had arrived before 1882.

In “Chop Suey as Imagined Authentic Chinese Food: The Culinary Identity of Chinese Restaurants in the United States” published in the Journal of Transnational American Studies, author Haiming Liu writes:

"Most Chinese immigrants learned the restaurant trade in the United States when other jobs were not available to them. After the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the economic recession in California in the 1870s, and especially the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the Chinese faced constant racial harassment and discrimination in their economic and social lives. Chinese concentration in the restaurant business illustrates how the racialized environment drove the Chinese into menial service occupations. Like the laundry, restaurant work became a trademark occupation of the Chinese. From 1900 to the 1960s, most Chinese restaurants in America were called chop suey houses, and chop suey was synonymous with Chinese food in the United States. When numerous chop suey houses spread across American cities, food became a tangible component of Chinese American ethnic identity."

Initially, most Chinese residents in Columbus worked in laundries. At one time, there were up to 40 Chinese laundries in the city. By 1968, only three remained, as the Chinese community had shifted into the food business. By 1996, Columbus food writer Doral Chenoweth reported that the city had more than 140 Chinese restaurants.

What is Chop Suey, Anyway?

Chop suey, meaning "odds and ends," originated from the Chinese dish chao zasui, which traditionally consisted of stir-fried animal intestines. The term "chop" is pronounced za in Mandarin, meaning "miscellaneous."

The origins of chop suey are believed to trace back to San Francisco around the time of the Gold Rush in the mid-1850s. While the exact inventor remains unknown, the dish quickly became widespread. "Chop suey" was an easy name for Americans to recognize and pronounce, leading it to become a defining feature of Chinese restaurants across the country.

Wong Chin Foo, one of the earliest Chinese American journalists, wrote in 1888: "A staple dish for the Chinese gourmand is Chow Chop Suey, a mixture of chicken livers and gizzards, fungi, bamboo buds, pig’s tripe and bean sprouts stewed with spices. The gravy of this is poured into the bowl of rice with some sauce, making a delicious seasoning to the favorite grain."

As the dish spread across the U.S., Chinese cooks adapted it using locally available ingredients. While every version was different, the common thread was a stir-fry technique using a wok and a flavorful sauce. The flexibility of chop suey allowed Chinese cooks to cater to American tastes.

In 1896, the visit of Chinese viceroy Li Hongzhang to New York City sparked a nationwide chop suey craze, leading even the mayor of New York City to visit Chinatown to try the dish. Its affordability and flavor helped Chinese restaurants expand beyond traditional Chinatowns. Around 1900, Chicago had just one Chinese restaurant, but by 1905 the number had grown to 40. Columbus likely followed a similar trajectory.

As chop suey gained popularity, the dish became more standardized. By the 1920s, typical ingredients included bean sprouts, celery, bamboo shoots, water chestnuts and mushrooms, with meats such as chicken, pork or beef replacing organ meats. The Michigan-based La Choy Corporation even began selling canned chop suey vegetables.

The First Chinese Restaurants in Columbus

It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when the first Chinese restaurant in Columbus opened, but the earliest listing in the City Directory appears in 1902 under the name of Song Lee, located at 146 ½ E. Town St. I believe this was one of several Chinese restaurants in operation at the time, based on newspaper clippings from the same year referencing other locations and alluding to multiple chop suey houses.

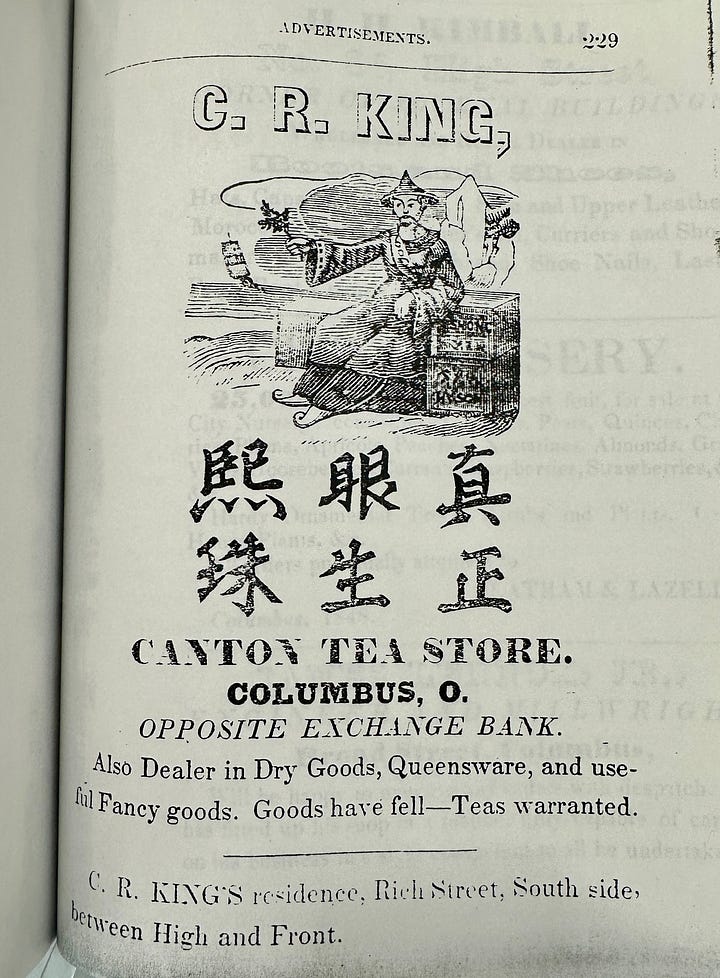

Unfortunately, the restaurant listings in the city directory are not comprehensive. Tea shops had been open for many years, with the earliest advertisement I found dating back to 1848, and there was a mention of an opium den being raided in 1898.

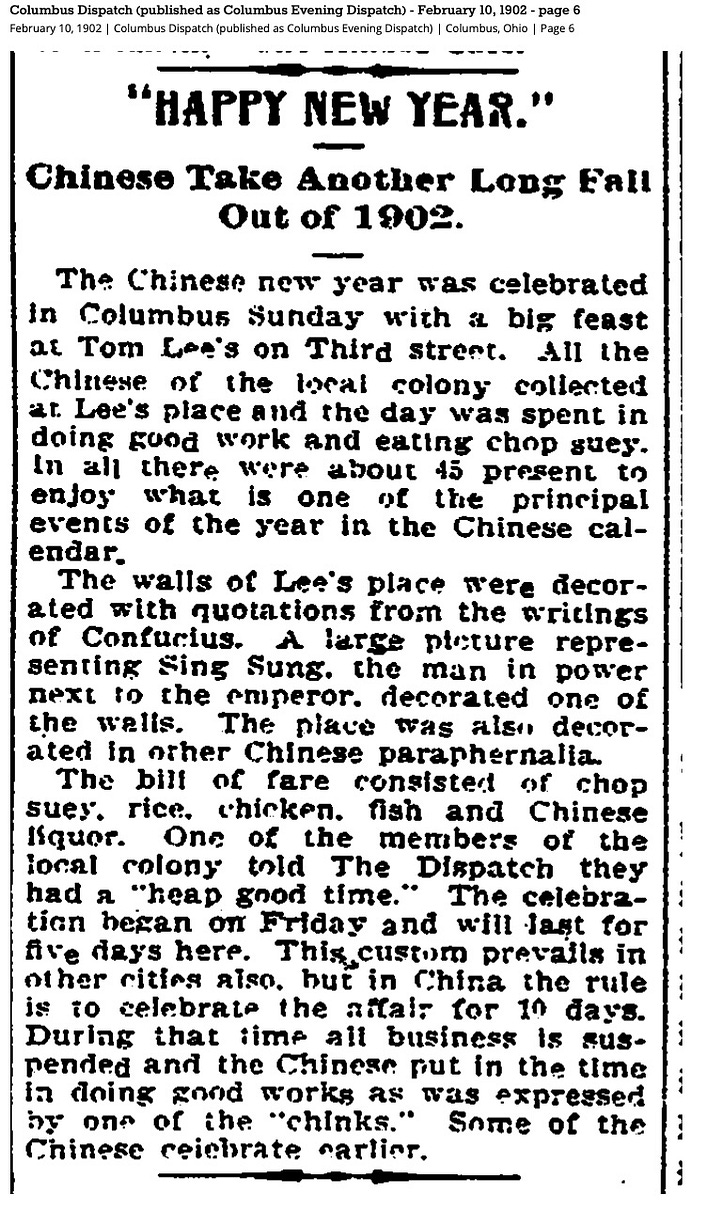

By 1902, the Chinese population of Columbus was estimated at around 40 people. (At the time, Chinese people were often referred to as "Celestials" in mass media, because in the 19th century China was romantically known as the Celestial Empire.) A Dispatch report from February 1902 describes a Lunar New Year celebration, complete with firecrackers. At this time, most Chinese residents in Columbus were bachelors, with few families present. The birth of the first recorded Chinese baby in Columbus was reported in 1905.

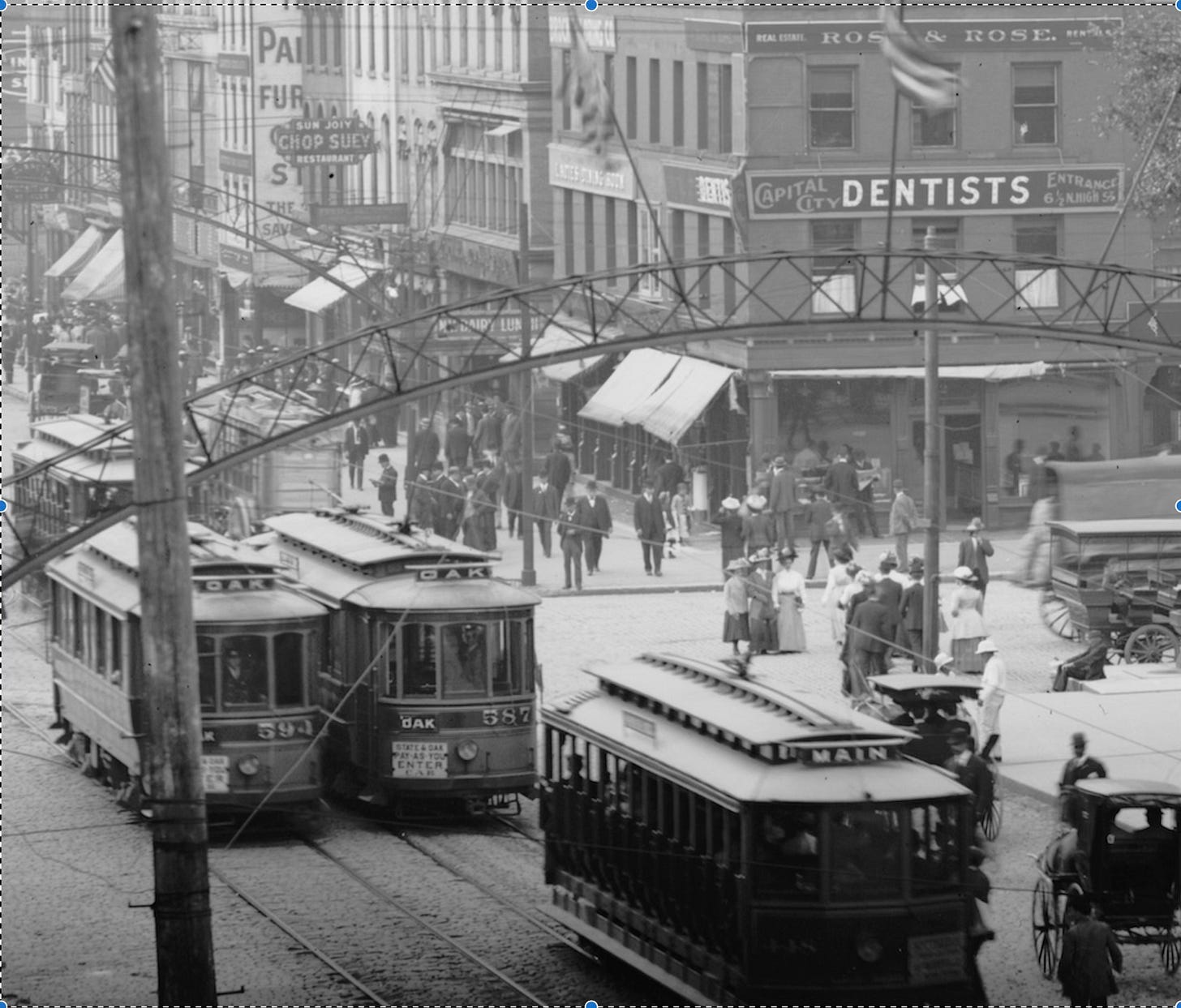

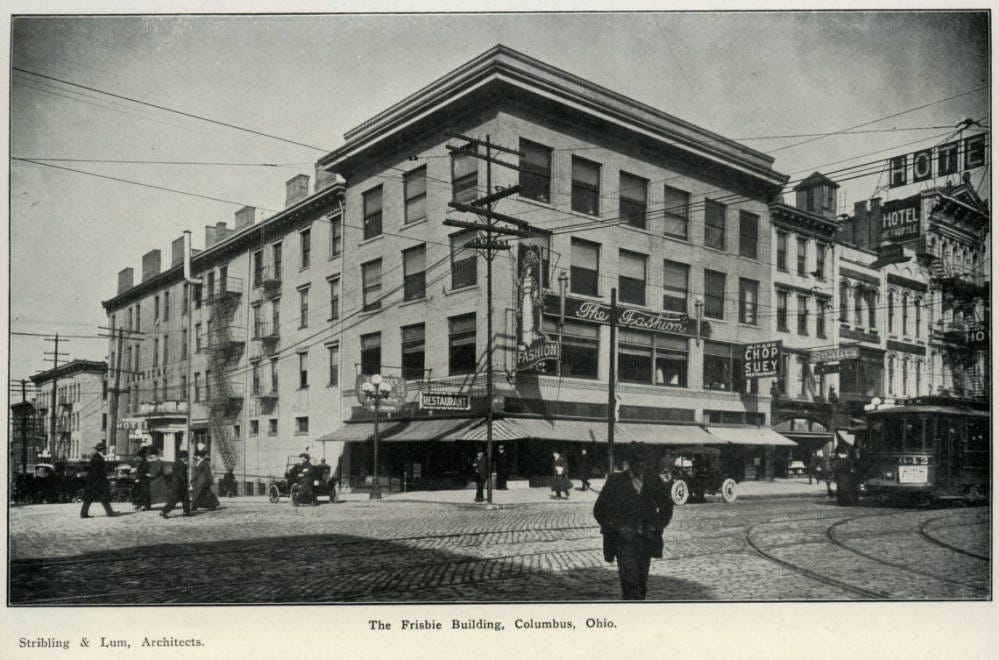

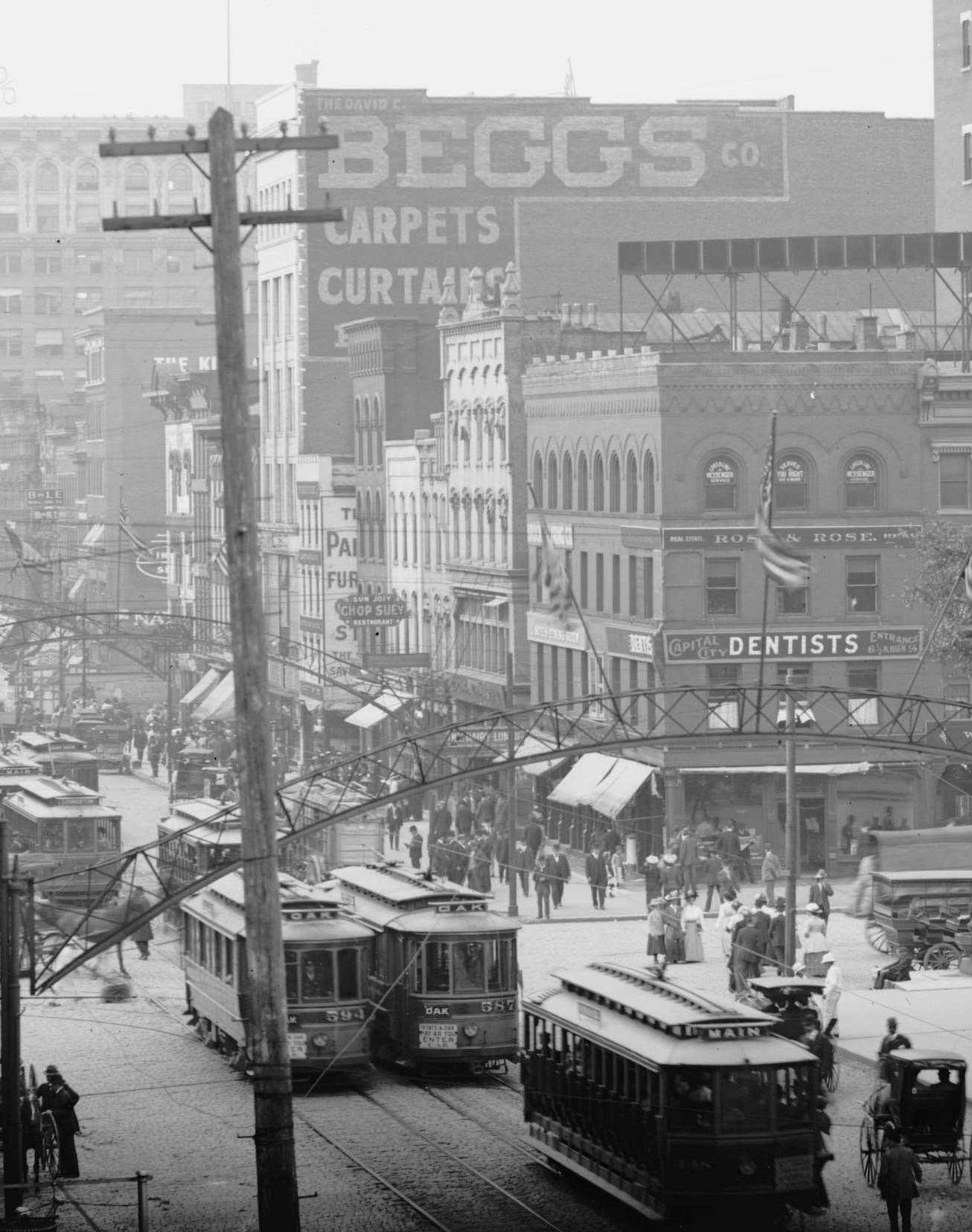

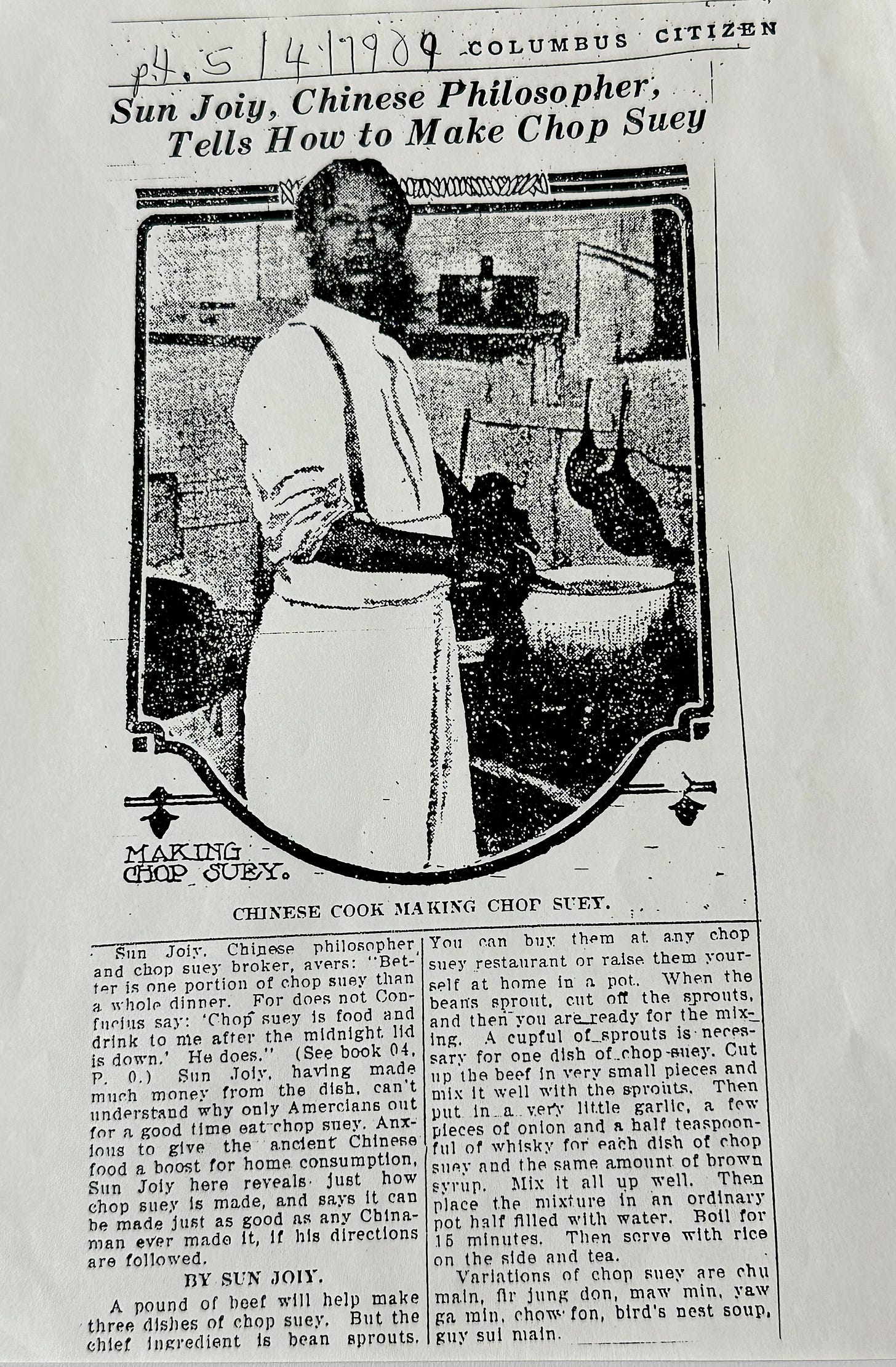

In October 1903, the Dispatch reported on a 12-course Chinese banquet hosted by chef Sun Joiy at "the well-known Chop Suey restaurant." The article stated, "Many of the guests had eaten the peculiarly palatable Oriental dishes before, but some were novices in Chinese cuisine, and to them, the affair was one of novelty and great pleasure." This banquet may have been a public relations effort to improve the restaurant's reputation following a police raid the previous month. In September 1903, Sun Joiy’s restaurant had been charged with violating the midnight closing ordinance and selling beer without a license.

A Few Other Notable Dates

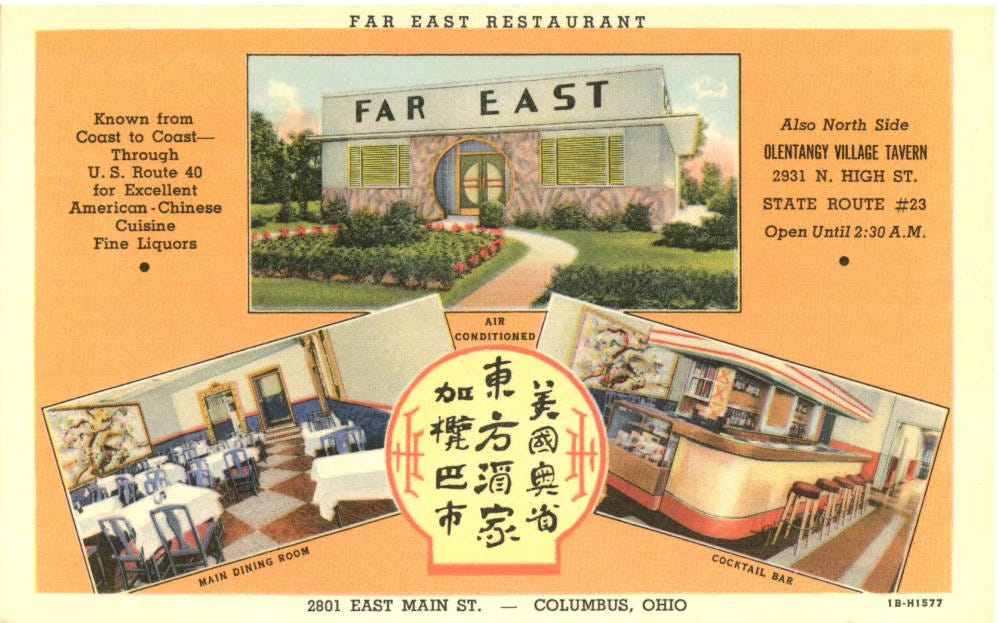

1929 – Far East Restaurant (2801 E. Main St.): Opened by Walter Ming in the same building now occupied by Wing’s Restaurant in Bexley, Far East initially did catering and sold imported foods. It later became a nightclub, and some credit it as the birthplace of war su gai. Far East closed in 1964.

1950 – Jong Mea Restaurant (747 E. Broad St.): Jong Mea replaced a former Chinese restaurant at the same location. Featured in “Lost Restaurants of Columbus,” it was a popular late-night destination, serving customers from 4 p.m. to 4 a.m. Jong Mea closed in 1996.

1956 – Ding Ho (120 Phillipi Road): The restaurant was first opened by Frank Yee and Clifford Yee (unrelated) in a converted gas station on West Broad. Now located on Phillipi Road, Ding Ho remains a family-run business, currently operated by Peter Yee’s twins, Steve and Lucy Yee.

1970 – Wing’s Restaurant & Bar (2801 E. Main St.): Wing Yee opened Wing’s in Bexley. It has since become known for having one of the most extensive Scotch collections in Central Ohio.

1987 – Hunan Lion (2038 Crown Plaza Drive): This Northwest Side institution was first opened by Allyson and Jason Chang. Former Dispatch restaurant reviewer Doral Chenoweth named Hunan Lion the city’s “first true gourmet Chinese restaurant.” In October 2023, the restaurant was damaged in a kitchen fire and has yet to reopen.

We’d love to hear your memories of Chinese restaurants in Columbus. What was the first Chinese restaurant you remember visiting? Let us know in the comments.

Notes

Around the Columbus Food & Drink Scene

Al Manakeesh, a Palestinian restaurant based out of Bridgeview, Illinois, is expected to open this weekend at 6181 Sawmill Rd. #A in Dublin. The new spot specializes in manakeesh (aka manakish), a Levantine flatbread that’s similar to pizza. Manakeesh toppings include za’atar and cheese, falafel and even chocolate. The restaurant also serves Jerusalem ka'ak (Jerusalem bagel) sandwiches.

Last week, Black Radish Creamery’s raclette took home second place in the raclette category at the highly competitive 2025 U.S. Championship Cheese Contest. You can find the award-winning cheese at Black Radish’s North Market Downtown shop, the BRC farm store in Alexandria, the Worthington Farmers Market and the new Charmy’s Market on Grant Avenue.

The Mexican food truck Orale Guey recently opened its first brick-and-mortar cafe at 3415 E. Broad St., formerly Block’s Bagels. The new restaurant specializes in breakfast and lunch dishes such as chilaquiles, pancakes, huevos rancheros, sopes, tortes and more. The cafe is open daily from 7 a.m. to 3 p.m.

I really really REALLY hope Hunan Lion returns. That was the fancy restaurant my grandparents would take our family to when they visited from Florida, and I have so many formative memories of the place.

This is from the Museum of Food and Drink, where I also learned this:

In the early 1900s, Chinese restaurants moved towards serving more than just the Chinese community to make a profit, which pushed two trends in my opinion - having two menus (an American one and a Chinese one) and possibly the historical reason for having extensively long menus.

Also due to the Exclusion Act, special visas were granted to merchants. "High grade" restaurants were federally added to the special visa in 1915. The increased the growth of Chinese restaurants in the 1920s.